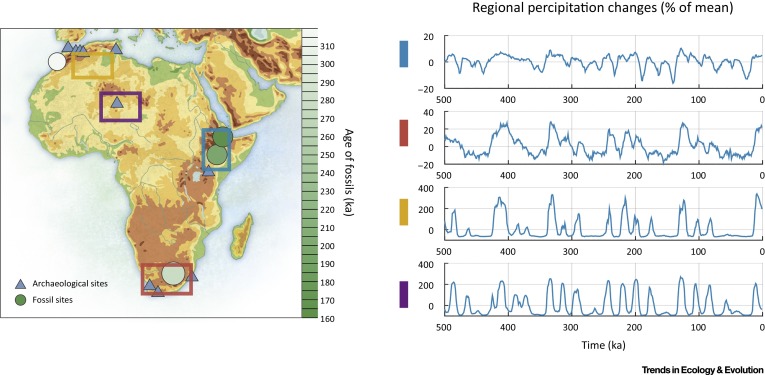

Across Africa, the virtual abandonment of handheld large cutting tools such as handaxes, and an increased emphasis on prepared core technologies and hafting,

marked a profound technological reconfiguration of hominin material

culture. These technological changes, which define the transition to the

Middle Stone Age (MSA), seem to have occurred across

Africa at a broadly similar time; for example at ∼300 ka both at Jebel

Irhoud, where they are found with early H. sapiens fossils [16xThe age of the hominin fossils from Jebel Irhoud, Morocco, and the origins of the Middle Stone Age. Richter, D. et al. Nature. 2017;

546: 293–296

Crossref | PubMed | Scopus (47) | Google ScholarSee all References][16], and at Olorgesailie in East Africa [30xLong-distance stone transport and pigment use in the earliest Middle Stone Age. Brooks, A. et al. Science. 2018;

360: 90–94

Crossref | PubMed | Scopus (4) | Google ScholarSee all References][30], and at ∼280 ka in southern Africa at Florisbad [31xDirect dating of the Florisbad hominid. Grün, R. et al. Nature. 1996;

382: 500–501

Crossref | PubMed | Scopus (113) | Google ScholarSee all References][31]. Currently, the earliest dates in West Africa are younger, at ∼180 ka, but the region remains very poorly characterized [32xThe West African Stone Age. Scerri, E.M.L.

Google ScholarSee all References][32]. The MSA is associated with H. sapiens fossils, but both H. naledi and H. heidelbergensis probably persisted into the late Middle Pleistocene.

Clear

regionally distinctive material culture styles, typically involving

complex stone tools, first emerged within the MSA. For example, the

Central African MSA includes heavy-duty axes, bifacial lanceolates,

backed flakes and blades, picks and segments, probably from at least the

late Middle Pleistocene [33xAcross rainforests and woodlands: a systematic reappraisal of the Lupemban Middle Stone Age in Central Africa. Taylor, N. : 273–300

Crossref | Scopus (7) | Google ScholarSee all References][33]. In the Late Pleistocene,

grassland and savannah expansion in North Africa led to dense human

occupation associated with specific regional technological features such

as tanged implements (Figure 2Figure 2) [34xThe North African Middle Stone Age and its place in recent human evolution. Scerri, E.M.L. Evol. Anthropol. 2017;

26: 119–135

Crossref | PubMed | Scopus (2) | Google ScholarSee all References][34].

At approximately the same time there was an emergence of comparably

distinctive industries in parts of southern Africa. As in North Africa,

some of these industries are also associated with other aspects of

complex material culture such as ochre, bone tools, shell beads, and

abstract engravings (Figure 2Figure 2) [35xIdentifying

early modern human ecological niche expansions and associated cultural

dynamics in the South African Middle Stone Age. d’Errico, F. et al. PNAS. 2017;

114: 7869–7876

Crossref | Scopus (9) | Google ScholarSee all References][35].

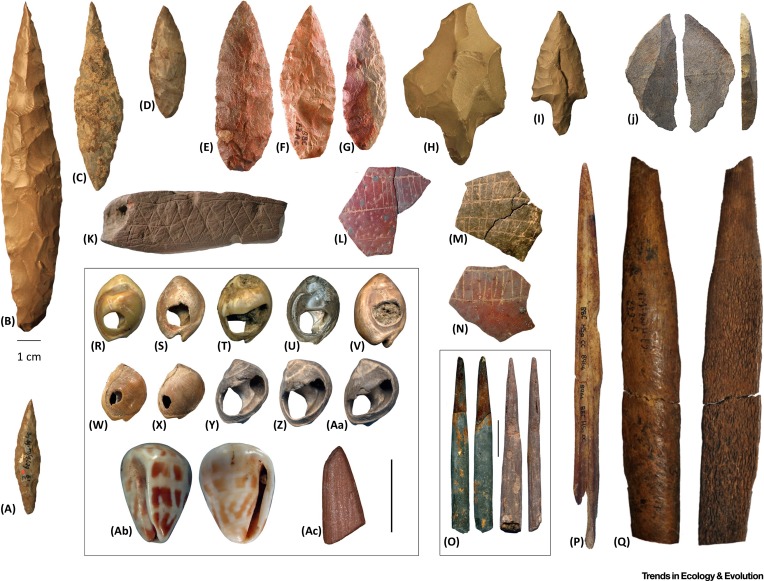

Figure 2

Middle

Stone Age Cultural Artefacts. (A–D) Bifacial foliates from northern

Africa (A, Mugharet el Aliya; B–D, Adrar Bous). (E–G) Bifacial foliates

from southern Africa (Blombos Cave). (H,I) Tanged tools from northern

Africa. (J) Segmented piece bearing mastic residue from southern Africa

(Sibudu). (K) Engraved ochre fragment (Blombos Cave). (L–N) Engraved

ostrich eggshell fragments from southern Africa (Diepkloof). (O,P) Bone

points from southern Africa (Sibudu and Blombos Cave, respectively). (Q)

Bone point from northern Africa (El Mnasra). (R–V) Perforated Trivia gibbosula

shells from northern Africa (R,S, Grotte de Pigeons; T–V, Rhafas, Ifri

n’Ammar, and Oued Djebbana, respectively). (W–Aa) Perforated Nassarius kraussianus shells from Blombos Cave. (Ab) Conus ebraeus

shell bead (Conus 2) from southern Africa (Border Cave). (Ac) Ochre

fragment shaped by grinding from southern Africa (Blombos Cave). All

scales are 1 cm. Boxed items indicate rescaled artefacts. Images

reproduced, with permission, from (A–D, H, I) The Stone Age Institute;

(E–G, J–P, Ac) from [35xIdentifying

early modern human ecological niche expansions and associated cultural

dynamics in the South African Middle Stone Age. d’Errico, F. et al. PNAS. 2017;

114: 7869–7876

Crossref | Scopus (9) | Google ScholarSee all References][35]; (Q) from [47xOsseous projectile weaponry from early to late Middle Stone Age Africa. Backwell, L. and d’Errico, F. : 15–29

Crossref | Scopus (8) | Google ScholarSee all References][47]; and (R–Ab) from [35xIdentifying

early modern human ecological niche expansions and associated cultural

dynamics in the South African Middle Stone Age. d’Errico, F. et al. PNAS. 2017;

114: 7869–7876

Crossref | Scopus (9) | Google ScholarSee all References, 47xOsseous projectile weaponry from early to late Middle Stone Age Africa. Backwell, L. and d’Errico, F. : 15–29

Crossref | Scopus (8) | Google ScholarSee all References, 48xAdditional evidence on the use of personal ornaments in the Middle Paleolithic of North Africa. d’Errico, F. et al. PNAS. 2009;

106: 16051–16056

Crossref | PubMed | Scopus (140) | Google ScholarSee all References].

Such

regionalization is typically linked with the emergence of ‘modern’

cognition. However, it arguably also reflects the interaction between

demographic variables (e.g., increased population density) [36xLate Pleistocene demography and the appearance of modern human behavior. Powell, A. et al. Science. 2009;

324: 1298–1310

Crossref | PubMed | Scopus (438) | Google ScholarSee all References, 37xThe Still Bay and Howiesons Poort: ‘Palaeolithic’ techno-traditions in southern Africa. Henshilwood, C.S. J. World Prehist. 2012;

25: 205–237

Crossref | Scopus (54) | Google ScholarSee all References, 38xCoalescence and fragmentation in the late Pleistocene archaeology of southernmost Africa. Mackay, A. et al. J. Hum. Evol. 2014;

72: 26–51

Crossref | PubMed | Scopus (61) | Google ScholarSee all References] and the learned traditions of long-lived regional subpopulations or demes (Figure 2Figure 2).

For example, northern and southern Africa, apart from being

geographically distant, were also separated by environmental factors as a

consequence of the expansion and contraction of forests in equatorial

Africa, synchronous with amelioration in northern Africa. Other factors,

such as habitat variability and adaptation to local environmental

conditions, are also likely to play some role in material culture

diversification.

Although geographical differences are

clear at the continental scale, localized spatial patterning is harder

to discern. Similarities between regions may have been produced by

occasional contact or by convergent adaptation to common environmental

conditions. In East Africa, for example, although there is certainly

some variation, there appears to be underlying continuity in material

culture throughout much of the MSA (e.g., [39xStone tool assemblages and models for the dispersal of Homo sapiens out of Africa. Groucutt, H.S. et al. Quat. Int. 2015;

382: 8–30

Crossref | Scopus (28) | Google ScholarSee all References][39]). In many regions, ‘generic’ MSA assemblages that do not carry an obvious signal of regionalization are common [40xEcological

risk, demography, and technological complexity in the Late Pleistocene

of Northern Malawi: implications for geographical patterning in the

Middle Stone Age. Thompson, J. et al. J. Quat. Sci. 2017;

33: 261–284

Crossref | Scopus (1) | Google ScholarSee all References][40].

In a cognitive model, these differences suggest that not all these

early populations manifested a ‘modern mind’. However, such assemblages

are augmented by shifting frequencies of tool types that appear to be

spatially or temporally indicative, and likely reflect demographic

factors. In some parts of Africa, the full suite of generalized MSA

characteristics continues largely unchanged until the

Pleistocene/Holocene boundary [41xPersistence

of Middle Stone Age technology to the Pleistocene/Holocene transition

supports a complex hominin evolutionary scenario in West Africa. Scerri, E.M.L. et al. J. Archaeol. Sci. Rep. 2017;

11: 639–646

Google ScholarSee all References][41],

matching the morphological patterns, and suggesting that the end of the

MSA may have been as structured and mosaic-like as its beginnings. This

view has support from LSA material culture. Despite superficial

similarities in LSA lithic miniaturization, the cultural record shows

continued differentiation and derivation into the Holocene, supporting

the biological evidence for variable population dynamics that did not

result in wide-scale homogenization [42xA demographic perspective on the Middle to Later Stone Age transition from Nasera rockshelter, Tanzania. Tryon, C.A. and Faith, J.T. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. 2016;

B 371

Crossref | PubMed | Scopus (9) | Google ScholarSee all References][42].

The

reasons for, and therefore implications of, the geographic and temporal

structuring of MSA cultural diversity are still poorly characterized

and likely reflect several processes. These include adaptations to

different environments [43xThe evolution of the diversity of cultures. Foley, R.A. and Mirazón-Lahr, M. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. 2011;

366: 1080–1089

Crossref | PubMed | Scopus (44) | Google ScholarSee all References][43]. Long-term, large-scale population separation may also have been the norm for much of Pleistocene Africa (Box 1;

i.e., isolation by distance and isolation by habitat, representing null

models to be rejected). Rare and spatially explicit models exploring

Pleistocene technological innovations have also linked cultural

complexity with variation in regional patterns of population growth,

mobility, and connectedness (e.g., [36xLate Pleistocene demography and the appearance of modern human behavior. Powell, A. et al. Science. 2009;

324: 1298–1310

Crossref | PubMed | Scopus (438) | Google ScholarSee all References, 44xCulture, population structure, and low genetic diversity in Pleistocene hominins. Premo, L.S. and Hublin, J.-J. PNAS. 2009;

106: 33–37

Crossref | PubMed | Scopus (62) | Google ScholarSee all References, 45xPopulation density, mobility, and cultural transmission. Grove, M. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2016;

74: 75–84

Crossref | Scopus (4) | Google ScholarSee all References]), supported by evidence of long-distance transfer of stone raw material (e.g., [46xThe

earliest long-distance obsidian transport: evidence from the ∼200 ka

Middle Stone Age Sibilo School Road Site, Baringo, Kenya. Blegen, N. J. Hum. Evol. 2016;

103: 1–19

Crossref | PubMed | Scopus (7) | Google ScholarSee all References][46]).

Box 1

+

Box 1

Isolation by Distance (IBD)

IBD

is the expectation that genetic differences correlate positively

geographic distances as a consequence of the fact that mating is more

likely to occur at shorter than longer distances. This concept, although

well established in genetics, is rarely applied to Pleistocene

archaeological and human fossil material, despite its potential value as

a null model for observed cultural or morphological differences between

materials from different sites [49xEstimating mobility using sparse data: application to human genetic variation. Loog, L. et al. PNAS. 2017;

114: 12213–12218

Crossref | PubMed | Scopus (0) | Google ScholarSee all References][49].

Because

archaeological problems are concerned with identifying the processes

that generate observed patterns of cultural variation over time and

space, the lack of equivalent null models is particularly problematic.

Processes generating cultural variation constitute a complex balance

between patterns of inherited knowledge, local innovation, modes of

cultural transmission, local adaptation, and shifting population

dynamics (e.g., population size, density, or mobility [36xLate Pleistocene demography and the appearance of modern human behavior. Powell, A. et al. Science. 2009;

324: 1298–1310

Crossref | PubMed | Scopus (438) | Google ScholarSee all References][36]).

Without null models of ‘cultural similarity’ as a baseline, it is

difficult to escape simplistic, narrative inferences about the past.

Similarly, human fossil data can be interpreted in several ways

depending on the taxonomy employed, but spatial variation is likely to

relate to the same factors that influence genetic similarities between

regional populations [50xDistance from Africa, not climate, explains within-population phenotypic diversity in humans. Betti, L. et al. Proc. R. Soc. 2009;

B 276: 809–814

Crossref | Scopus (77) | Google ScholarSee all References][50].

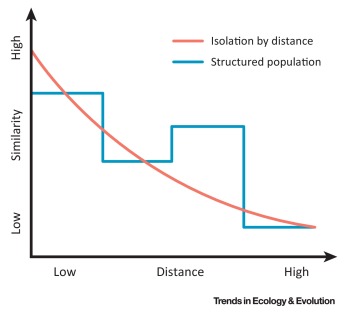

In

an archeological context, the expectation of an IBD model is that

cultural similarity will decrease with distance, with a degree of

spatial autocorrelation (e.g., [51xIsolation-by-distance, homophily and ‘core’ vs. ‘package’ cultural evolution models in Neolithic Europe. Shennan, S.J. et al. Evol. Hum. Behav. 2015;

36: 103–109

Abstract | Full Text | Full Text PDF | Scopus (16) | Google ScholarSee all References][51]).

This expectation represents the simplest explanation of the observed

variation. If this null model does not provide an adequate explanation

of the data, more complex models can be invoked to explain patterns

observed either in the residuals from the null model or in the raw data

as a whole. For example, a more complex population structure can be

theoretically differentiated from an IBD model if patterns of spatial

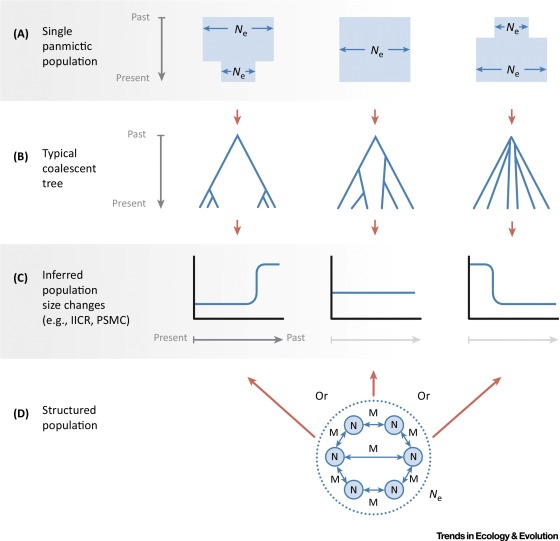

autocorrelation are discrete rather than continuous (Figure IFigure I),

pointing towards the formation of distinct biological or cultural

clusters which may correlate with other features (e.g., genetic,

morphological, or environmental). Many factors could promote the

formation of such clusters, including assortativity by cultural

similarity, or conformity to local norms of, for example, tool

production.

Figure I

Simple

IBD Model with Cultural Data. Note that similarity can increase with

distance under some circumstances, for example when similar habitats are

separated by considerable distances, with areas of different habitat

types being located between them.

Major

new archaeological research directions should include: (i) unraveling

the relative contributions of different African regions/habitats to

recent human evolution; (ii) understanding shifting patterns of

population structure through the differential appearance, expansion,

contraction, and disappearance of regionally distinct artefact forms (Box 1);

and (iii) exploiting the growing interface between archaeology,

ecology, morphology, and genetics to explore the extent to which

material culture patterning is coupled or decoupled from these

associated (but potentially independent) axes.

Article Info

Article Info