Evidence suggests Toba volcanic winter was less lethal than thought

Researchers find at least one human population thrived during a 1000-year volcanic winter. Richard A Lovett reports.

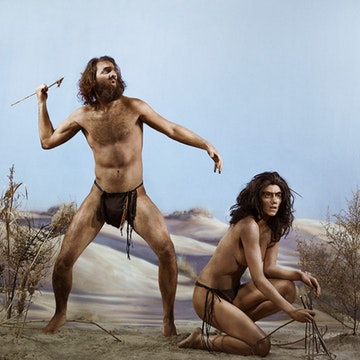

Scientists studying two archaeological sites near the extreme southern point of South Africa have discovered that early humans living there appear to have been unaffected by a supervolcano eruption so powerful that many experts thought it might nearly have killed off our entire species.

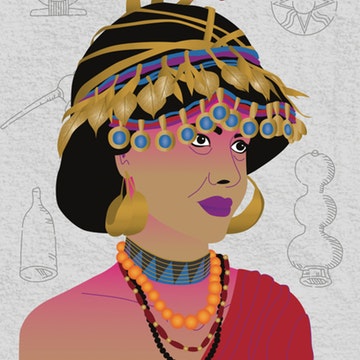

The volcano, known as Toba, is on the Indonesian island of Sumatra. About 74,000 years ago, it exploded in a blast that erupted about 2800 cubic kilometres of magma, including hundreds of cubic kilometres of volcanic ash. Scientists have proposed that it caused a multi-year “volcanic winter” and may have affected the Earth’s climate for a millennium. Some believe this may have contributed to a “genetic bottleneck” in which genetic studies suggest that 50,000 to 100,000 years ago, the entire human population may have dipped to as low as a few thousand.

But whatever happened elsewhere, Toba’s effects might not have been all that catastrophic in some parts of what is now South Africa.

Working at a cave known as Pinnacle Point and a nearby “outdoor activity” area known as Vleesbaai, researchers report identifying microscopic fragments of volcanic ash at both sites and chemically tying them to the Toba eruption. The results are published in the journal Nature.

Rather than being associated with death and destruction, these shards dated to times during which the human populations at these two sites continued to thrive. In fact, at Pinnacle Point, there appeared to have been an increase in human presence, as measured by the number of tools, fires, and animal bones.

“Human users of the cave were not (measurably) affected by the Toba eruption,” says Christine Lane, a professor of geography at the University of Cambridge, UK, who was a member of the study team.

The new study supports prior work at Lake Malawi, the southernmost lake in Africa’s Great Rift Valley, in which Lane and others found Toba shards and compared their stratigraphic location with markers of the local climate, before and after the eruption. That study did not focus on human habitation sites, but did find that, at least in the vicinity of Lake Malawi, the Toba eruption was not accompanied by a major change in sediment composition or evidence for substantial temperature change.

Lane cautions that it’s too early to read a lot into these findings. Perhaps, she says, Toba eruption wasn’t as globally catastrophic as previously suspected, and therefore didn’t create the genetic bottleneck. Or perhaps it didn’t affect all parts of East Africa equally. Perhaps the people living happily on the southern tip of South Africa might have been one of many such groups scattered across the continent. Then again, they might have been our species’ only survivors.

The answer, she and her colleagues say, will come by searching for Toba ash in other archaeological sites, looking to see how well people living there did, or didn’t, survive.

Martin Williams, an emeritus professor of geography, environment and population at the University of Adelaide, South Australia, who was not a member of the study team, agrees that caution is in order.

Finding Toba ash in South Africa, 9000 kilometres away from the source, he says, is “a brilliant achievement”. But the fact that people thrived at these two sites doesn’t mean the eruption didn’t have an enormous impact on the global climate.

Toba, he says, dropped a whopping 10 to15 centimetres of ash all the way across India. It produced dry, cold conditions in Asia, plus a sharp fall in temperatures recorded in Greenland ice cores. Cave deposits in New Mexico, US, show that it was followed by prolonged dry conditions, half a globe away.

Such effects, he says, may have bypassed the people at Vleesbaai and Pinnacle Point. “People living on the coast in a well-watered area, with adequate supplies of marine food as well as plant and animal resources from the land would have been well buffered from any perturbations that Toba may have triggered,” he says.

What’s needed to piece all of this together is better information about local and regional environmental changes. “Only then is it sensible to consider possible climate factors and causes,” he cautions.

Lane concurs. “Currently we do not have a record with the resolution to study the individual years following the Toba eruption,” she says. “It’s extremely hard to work at that resolution so far back in time.”

Among other things, she notes, such important factors as the time of year at which the eruption occurred are unknown: “While we can infer from the evidence in southern Africa that the impacts there must have been only short-lived and patchy, there may be different stories to tell from other regions.”

The possible scenarios are stark. Perhaps our ancient forebears sailed through the aftermath of the eruption at many locations. Or perhaps the only thing that saved humanity from extinction were the few who hunkered down on the South African coast until the aftermath of the super-volcano cleared and we began our historic spread, out of Africa and into the farthest points on the globe.